The Attention Economy Ate Your Agency

Robert Kenfield | 6 mins read | November 5, 2025

Early productivity software had a clear relationship with users: you told it what to do, and it did it.

You entered an appointment, and it reminded you at the scheduled time. You created a task list, and it stored your items. You wrote a note, and it saved your words.

The tool was an extension of your will, a way to externalize memory and coordinate complexity. The relationship was transactional and transparent: you provided input, the tool provided output, and you remained in control of the entire interaction.

This changed fundamentally with the rise of what Harvard Business School professor Shoshana Zuboff calls "surveillance capitalism," business models that profit from predicting and modifying human behavior rather than simply providing services.

Around the mid-2010s, productivity apps began incorporating machine learning and behavioral analytics. The stated goal was "personalization," making tools more helpful by adapting to individual patterns.

But personalization required data. Lots of data. Continuous data.

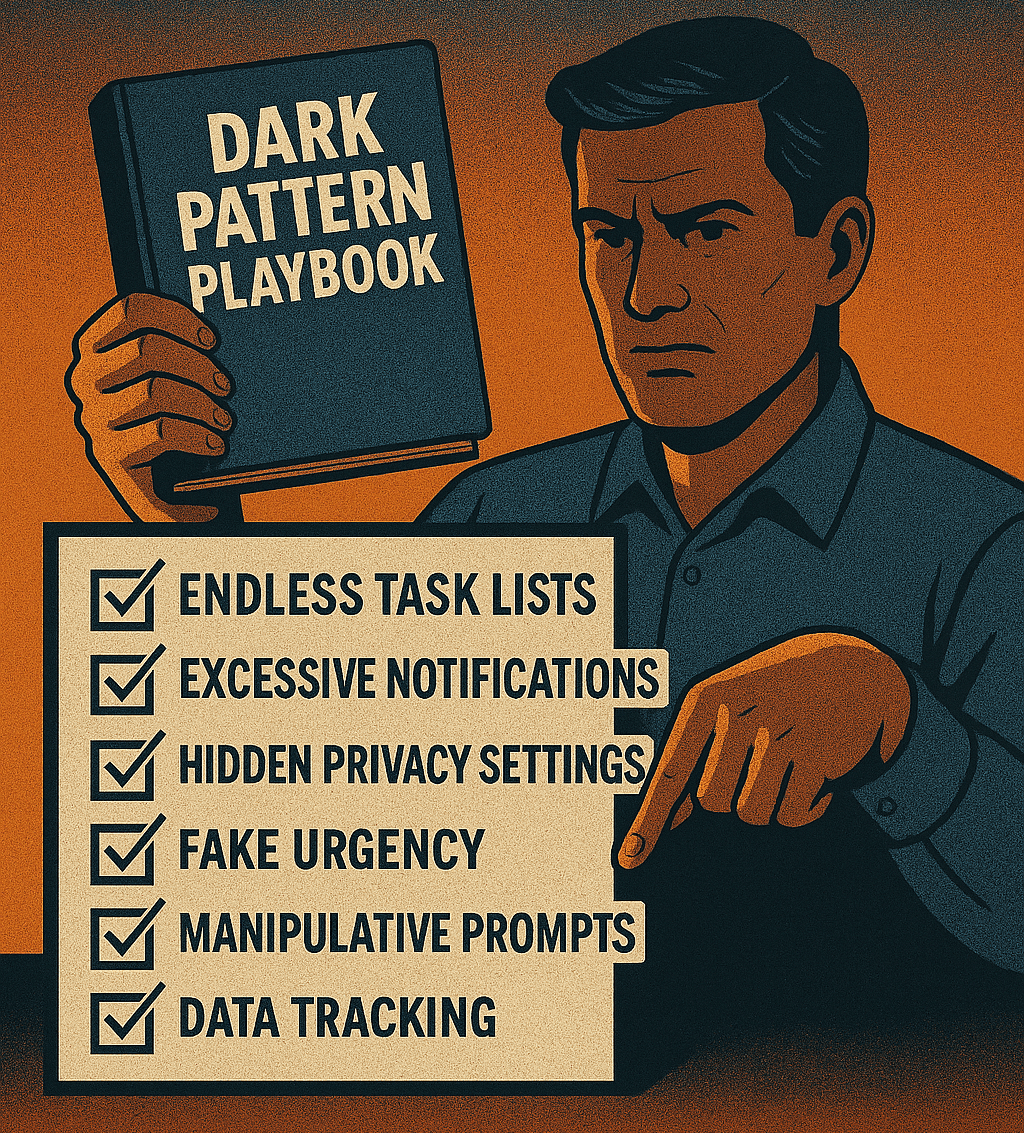

To personalize your experience, apps needed to know:

What you click on and when

How long you spend on different tasks

Which features you use and which you ignore

What time of day you're most active

What patterns precede task completion or abandonment

Who you interact with and how frequently

What content you create and modify

Where you are when you use different features

This data collection happened silently, continuously, automatically. You agreed to it somewhere in a terms of service document you didn't read. Most people still don't realize how comprehensive this surveillance has become.

Your productivity apps now know more about your daily patterns than your closest friends or family members.

The data collection itself might seem benign, after all, if it makes the app more helpful, what's the harm?

The problem emerges in what happens next: prediction.

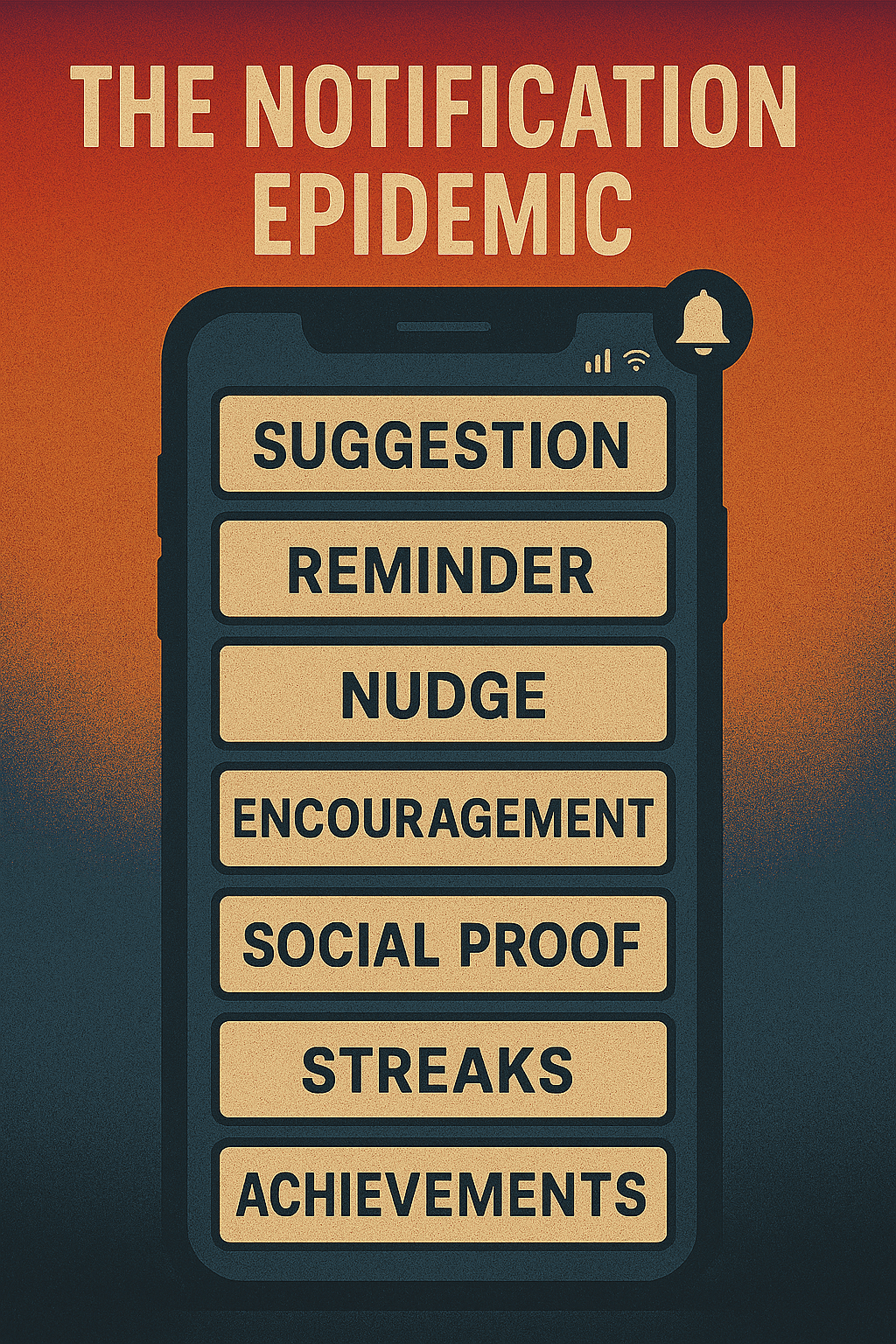

Once an app has collected enough behavioral data, machine learning algorithms can predict what you're likely to do next, what you'll want to work on, when you'll be most receptive to notifications, what features you'll use, what you'll ignore.

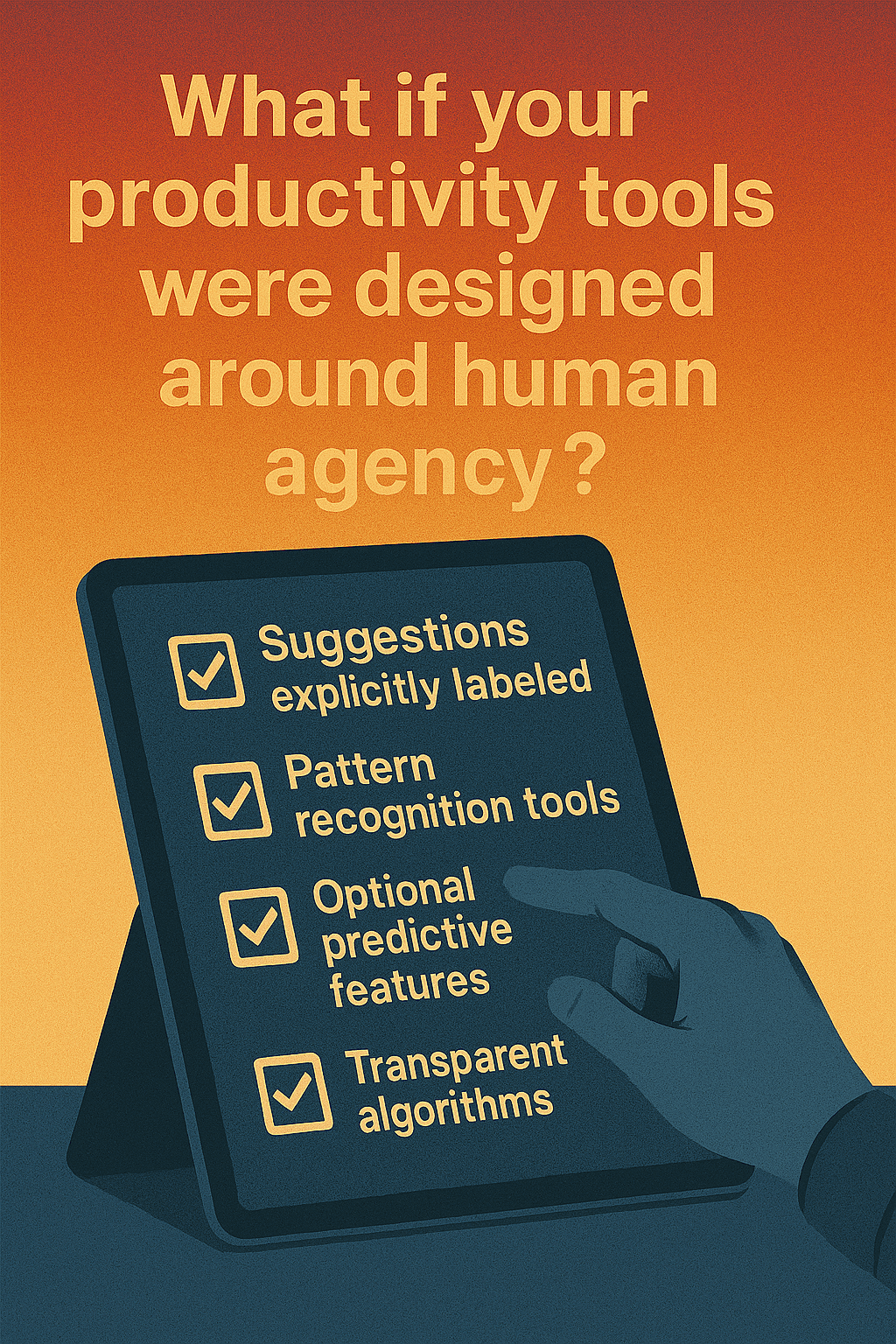

These predictions sound useful. And sometimes they are. Getting a reminder to leave for an appointment that accounts for current traffic is genuinely helpful.

But prediction fundamentally changes the nature of the tool. It's no longer simply executing your commands, it's anticipating your needs, interpreting your desires, and making choices about what to present to you and when.

The tool is no longer purely serving you. It's increasingly impacting how and what you decide.

The most sophisticated aspect of modern productivity apps is how they preserve the illusion of agency while actually constraining it.

The app offers "intelligent suggestions" for what to work on next. You can ignore them, of course. You're still in control, right?

Except the suggestions aren't neutral. They're algorithmically optimized based on what will keep you engaged with the app. They nudge you toward certain types of activities, certain working patterns, certain rhythms of engagement.

Research in behavioral economics shows that default options and suggested actions profoundly shape behavior, even when people believe they're making free choices. When your task manager suggests what you should do next, most people follow the suggestion most of the time, not because it's actually their highest priority, but because the cognitive effort of deciding independently is greater than accepting the algorithm's choice.

You're not being forced. But you're being shaped.

The app learns your patterns and feeds them back to you as recommendations, creating a reinforcing loop where you become more predictable over time, making the predictions more accurate, which makes you rely on them more, which makes you more predictable.

Your behavior becomes a script written by an algorithm analyzing your past actions.