The Collaborative Intelligence Revolution

Robert Kenfield | 7 mins read | December 30, 2025

The Stanford Life Design Lab's research revealed something that contradicts productivity culture's individualism: people who approach their lives with design thinking principles report higher life satisfaction, but only when they engage in what the researchers call "radical collaboration."

This isn't casual social interaction. It's the recognition that:

You can't design your life in a vacuum because your life is inherently social

The patterns that work for you often emerged from others' experiments

Your discoveries can help others who face similar challenges

Iteration and improvement happen faster through shared learning

Meaning itself emerges through connection and mutual support

The Stanford team found that isolated individuals using design thinking principles showed modest improvements. But people engaged in collaborative design practice, sharing approaches, giving feedback, adapting each other's methods, showed dramatically better outcomes across wellbeing measures.

The difference wasn't just magnitude, it was qualitative. Collaborative practitioners reported that the process itself became meaningful, not just the outcomes.

Research from MIT's Center for Collective Intelligence demonstrates that groups can solve complex problems better than even the smartest individuals, but only under specific conditions.

Anita Woolley and Thomas Malone's studies, published in Science, identified what creates "collective intelligence": groups that perform consistently well across different types of problems share certain characteristics:

Equal participation: No single voice dominates

Social sensitivity: Members are attuned to each other's responses

Diversity of perspective: Different viewpoints and approaches represented

Shared purpose: Clear common goals with individual autonomy

Life design, with its complexity, contextual variation, and personal meaning, is exactly the kind of problem where collective intelligence outperforms individual expertise.

No single "productivity expert" can prescribe what will work for your specific combination of chronotype, work demands, relationship responsibilities, health needs, and life stage. But a community of people experimenting with different approaches and sharing what works can generate insights that benefit everyone.

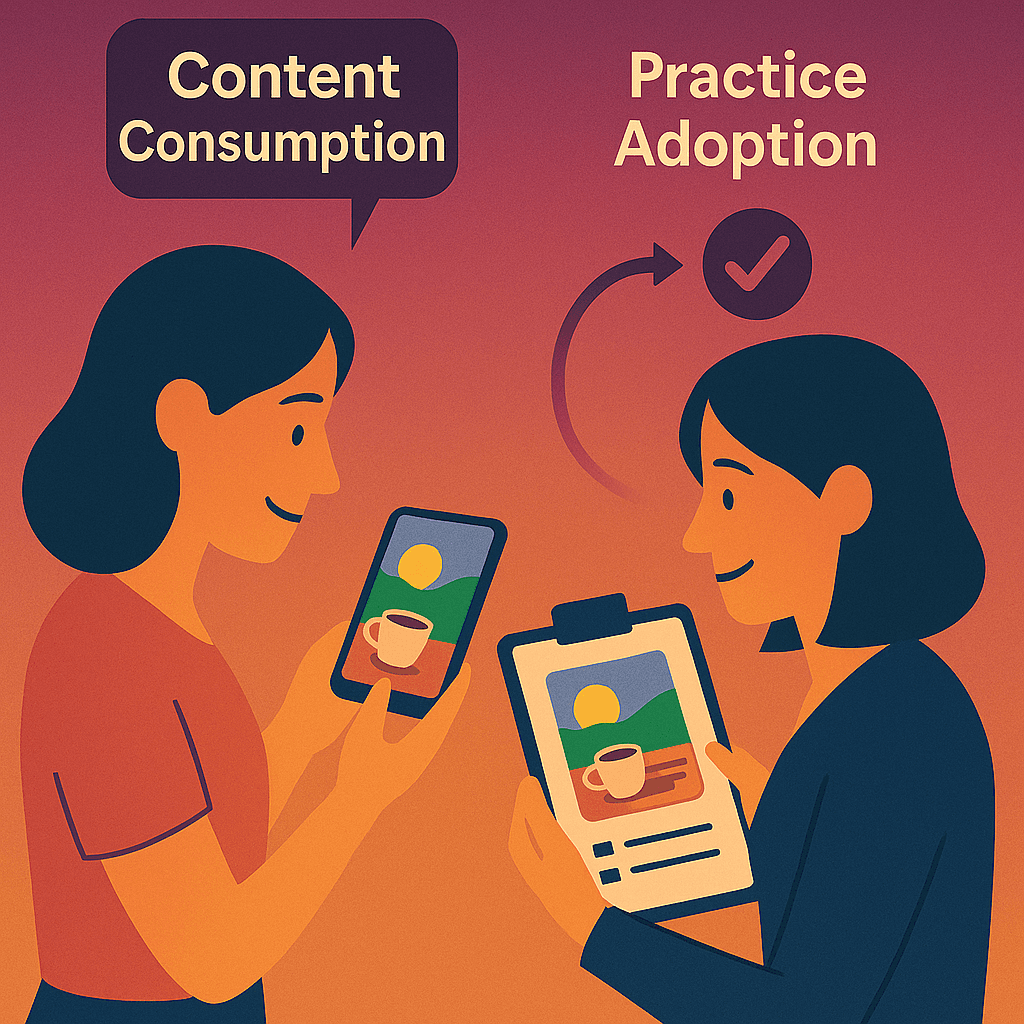

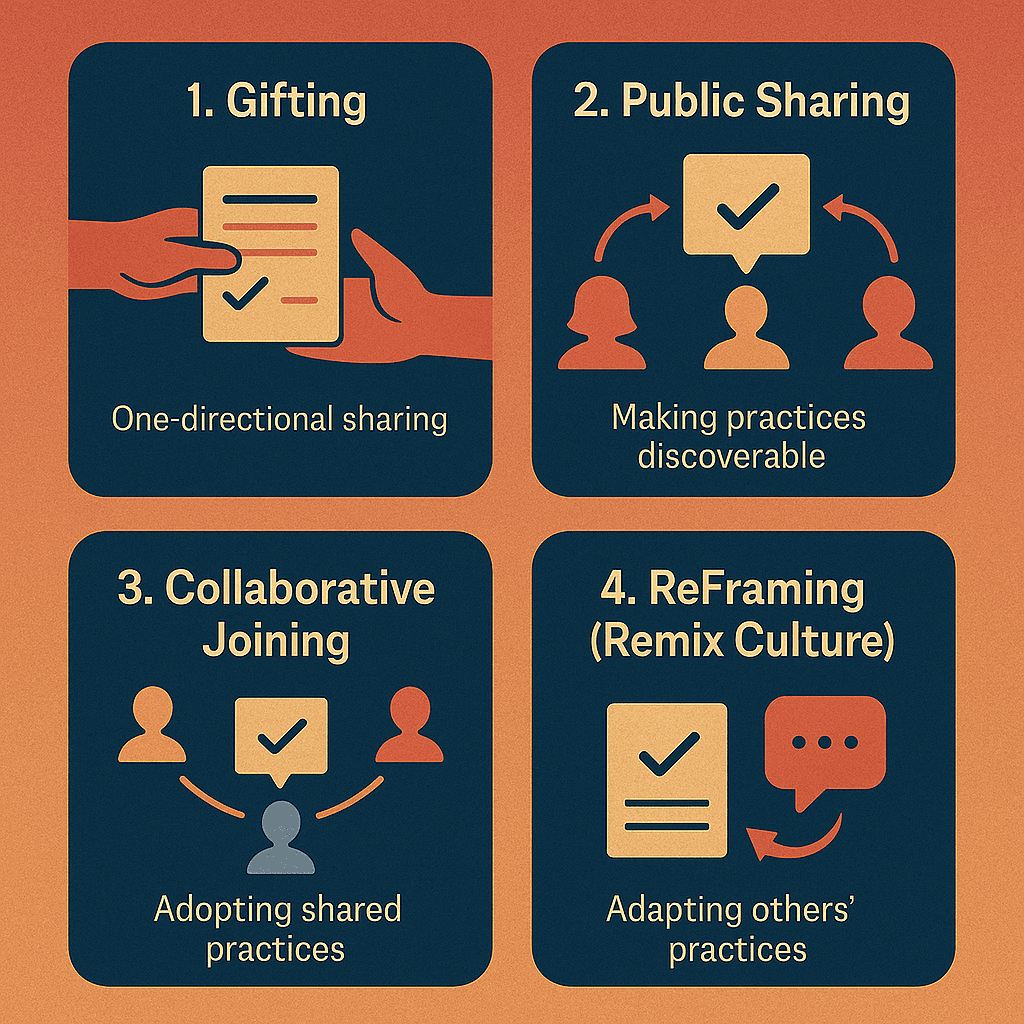

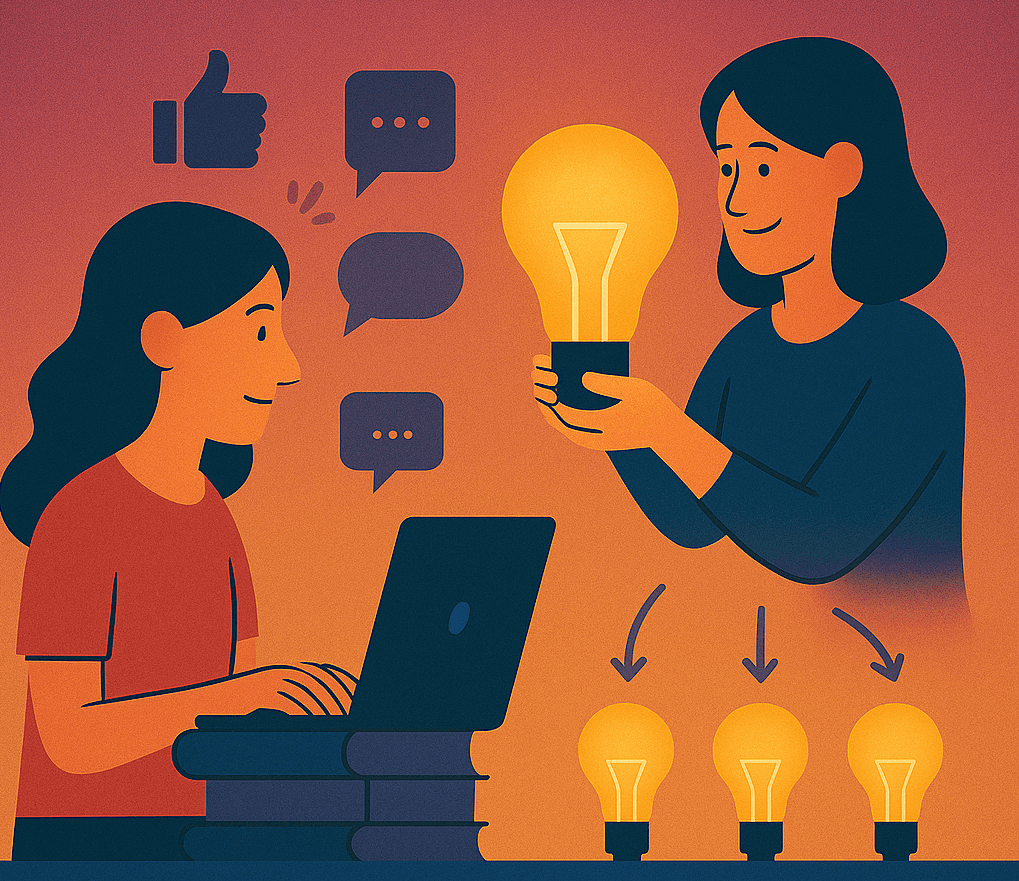

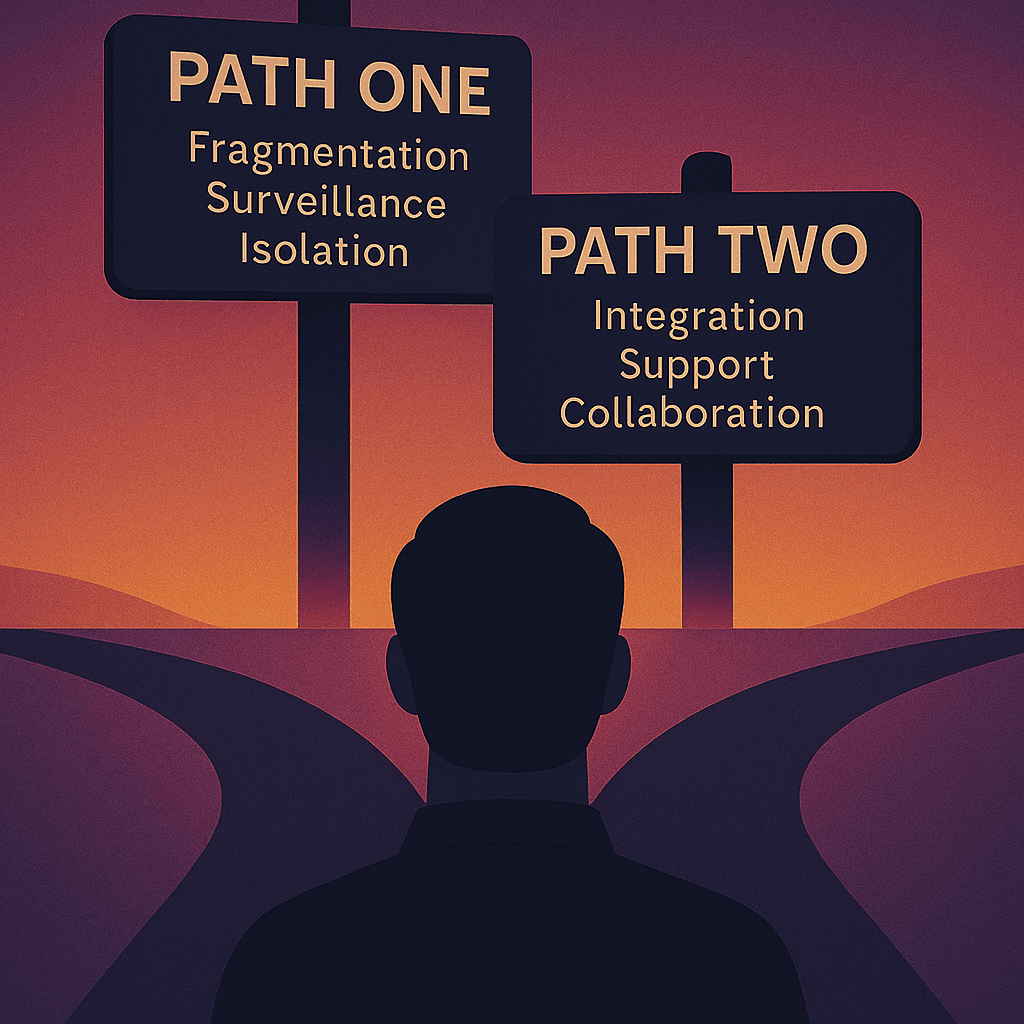

Social media has trained us to think of "sharing" as posting content for consumption: photos of our vacation, thoughts about our day, links to articles.

But life design requires something different: sharing practices for adoption and adaptation.

The difference is profound:

Content consumption is passive. You read about someone's morning routine and think "that's nice" or "I should try that someday." Maybe you feel inspired. But inspiration alone rarely changes behavior.

Practice adoption is active. Someone shares their morning routine in a format you can actually implement, complete with timing, visual representation, practical details, and context about why it works for them. You adopt it, adapt it to your situation, use it, improve it, and potentially share your version with others.

This is what technologists call "actionable knowledge", not information about what people do, but structured practices others can actually use.

Current social platforms don't support this. Instagram shows you someone's beautiful morning but doesn't give you a way to adopt and adapt their practice. LinkedIn shares productivity advice but provides no mechanism for collaborative improvement of actual routines.

The $250 billion creator economy reflects demand for actionable wisdom, but most creators are stuck offering inspiration and advice because platforms don't support practice sharing.

These social mechanics naturally evolve into what we might call a "marketplace of practices", not primarily commercial, but a collaborative ecosystem where effective approaches to living can be shared, tested, improved, and distributed at scale.

This differs fundamentally from traditional content platforms:

Practice vs. Information: Instead of consuming content about life design, people adopt actual practices that integrate directly into daily experience.

Evolution vs. Consumption: Practices improve through community use and adaptation rather than remaining static content created by individual experts.

Attribution vs. Ownership: Creators receive credit and can benefit from practice success while encouraging adaptation and improvement by others.

Community vs. Individual: The most effective practices often emerge through community collaboration rather than individual expertise.

Research in open-source software development shows that distributed collaboration consistently produces better outcomes than isolated development, when the right social architecture supports it.

Life design practices can follow the same model: shared, adapted, improved through collective intelligence rather than prescribed by isolated experts.