Life Design

Robert Kenfield | 7 mins read | December 10, 2025

Here's the insight that changes everything: you're already designing your life, whether you realize it or not.

Every morning you wake up and, consciously or unconsciously, make choices about how to spend your time, attention, and energy. You decide what matters, what to prioritize, what to defer, what to abandon.

You design patterns: morning routines, work rhythms, relationship practices, health habits. These patterns aren't random, they reflect (or betray) your values, your aspirations, your understanding of what makes life meaningful.

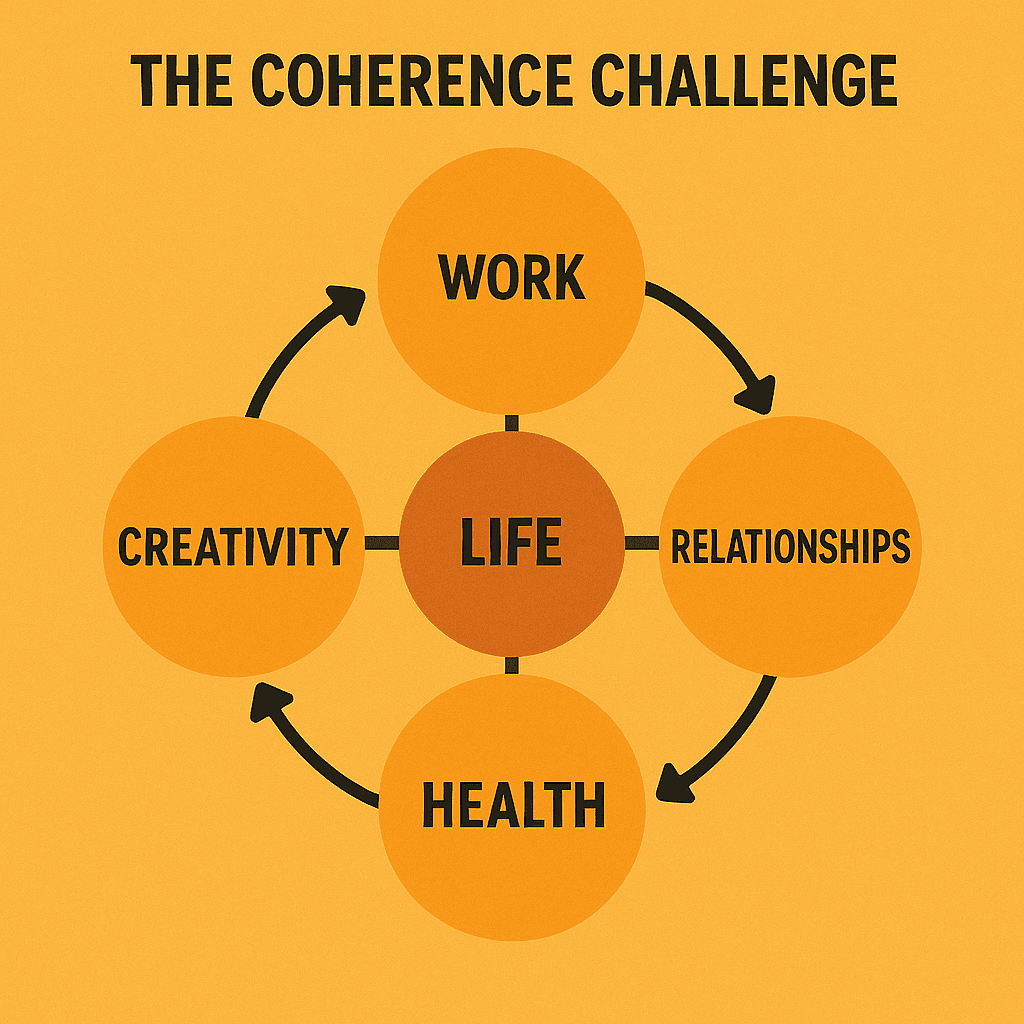

The question isn't whether you're a life designer. You are one, by necessity. The question is whether you're designing consciously or unconsciously, with support or despite obstacles, in alignment with your values or contradiction to them.

Productivity tools assume you need help executing pre-determined tasks. Life Design recognizes you need help with something more fundamental: making conscious choices about how to shape experience itself.

The concept of "life design" emerged from the Stanford Life Design Lab, where designers Bill Burnett and Dave Evans applied design thinking principles to the challenge of creating meaningful lives.

Their research, documented in Designing Your Life, revealed something profound: the same principles that work for designing products work for designing lives, but only when you stop treating life as a problem to solve and start treating it as a possibility to explore.

This shift is crucial. Problems have solutions. You optimize, execute, complete. But lives aren't problems, they're ongoing creative practices. You don't "solve" your life. You design it, iterate it, evolve it.

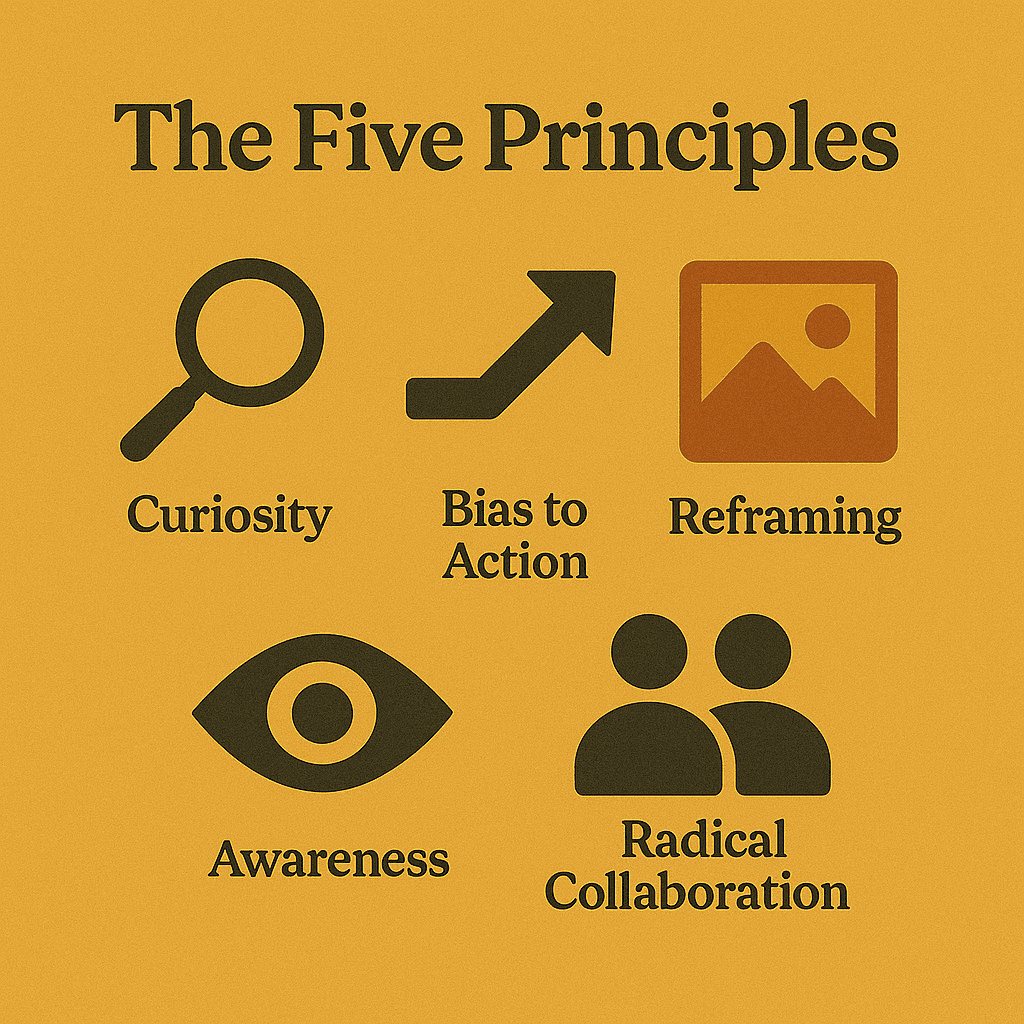

The Stanford team identified five core principles that distinguish life design from traditional productivity approaches:

1. Curiosity

Life design begins with curiosity rather than fixed assumptions about what should work. Instead of implementing other people's productivity systems, you explore what actually works for you in your specific context.

This means experimenting: trying different approaches, noticing what energizes versus drains you, discovering rather than prescribing. Productivity says "here's the system." Life Design asks "what if we tried this?"

2. Bias to Action

Rather than endless planning and analysis, life design emphasizes rapid prototyping. Test small experiments. Try things. Learn from real experience rather than hypothetical optimization.

This inverts the productivity paradigm. Productivity says "plan thoroughly, then execute." Life Design says "try quickly, learn continuously, adjust frequently."

A life design approach to morning routines doesn't start with researching the perfect routine, it starts with trying something tomorrow morning and noticing how it feels.

3. Reframing

When stuck, life design practitioners reframe the question rather than pushing harder with the same approach. If "how do I fit everything in?" feels impossible, reframe to "what actually matters enough to protect?"

This acknowledges that sometimes the problem definition itself is wrong. Productivity accepts the problem as given and optimizes execution. Life Design questions whether you're solving the right problem.

4. Awareness

Life design requires paying attention to what actually happens, not just what you plan or intend. How do different activities affect your energy? Which relationships nourish versus drain? What patterns serve versus undermine flourishing?

This means tracking quality of experience, not just completion metrics. Productivity measures what you did. Life Design asks how it felt and whether it mattered.

5. Radical Collaboration

Perhaps most importantly, life design recognizes that meaningful lives are created in relationship with others, not in isolation. You can't design your life alone, you're always designing within communities, relationships, and shared practices.

This fundamentally challenges productivity's individualistic optimization. Productivity assumes isolated actors maximizing personal efficiency. Life Design recognizes that meaning emerges through connection and collaboration.

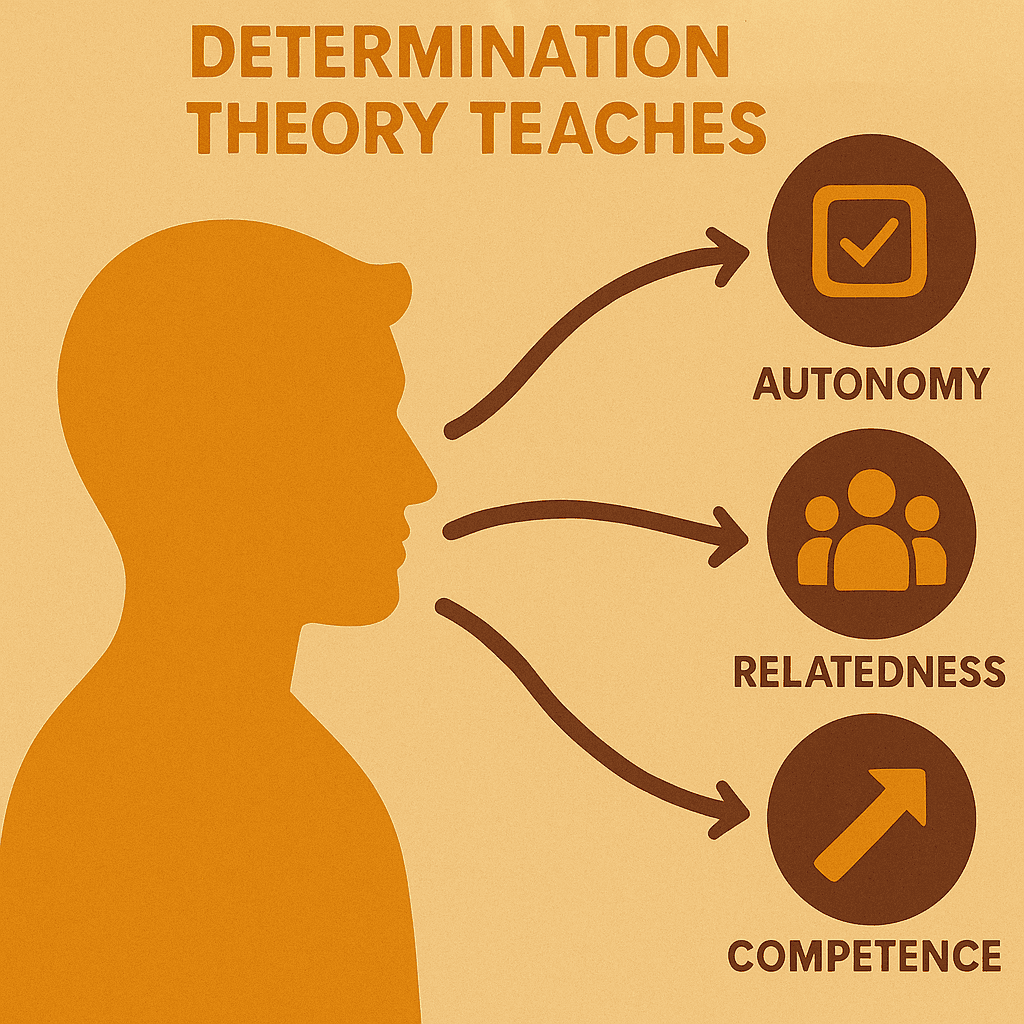

The psychological foundation for life design comes from decades of motivation research, particularly Self-Determination Theory developed by psychologists Edward Deci and Richard Ryan.

Their research identifies three fundamental psychological needs that drive intrinsic motivation and wellbeing:

Autonomy: Acting from choice and values, not external pressure

Competence: Experiencing growth, progress, and mastery

Relatedness: Connecting actions to others and larger purposes

When these needs are met, people experience what researchers call "eudaimonic wellbeing", flourishing that comes from meaning, growth, and authentic living rather than just pleasure or comfort.

Productivity tools, as we've explored, systematically undermine all three needs.

Life Design tools must actively support them:

Autonomy through conscious choice-making rather than algorithmic prediction

Competence through meaningful progress rather than binary completion

Relatedness through social practice rather than isolated optimization