Visual Thinking

Robert Kenfield | 7 mins read | December 17, 2025

In 1976, cognitive psychologists Lionel Standing, Jerry Konezni, and Ralph Norman Haber conducted a remarkable experiment. They showed participants 10,000 pictures over several days, spending just a few seconds on each image.

Days later, when tested on their recognition of these images mixed with new ones, participants achieved 83% accuracy.

Think about that: after seeing 10,000 images for mere seconds each, people could correctly identify most of them days later.

When researchers tried the same experiment with words instead of pictures, recognition rates plummeted. Studies consistently show that people remember pictures 65% better than words after three days, even when the words describe the same content as the pictures.

This isn't a small effect. It's what psychologists call the "picture superiority effect," and it reveals something fundamental about how human memory and cognition work.

Beyond memory, visual processing operates at remarkable speeds that text simply cannot match.

Research in visual neuroscience shows that humans can recognize objects in images in as little as 13 milliseconds, faster than a single eye blink. MIT neuroscientists found that the brain can process and understand the essence of a visual scene in a fraction of a second.

This rapid visual processing isn't just about recognition, it's about comprehension. When you glance at an image, you immediately grasp multiple dimensions of information: spatial relationships, emotional tone, context, and meaning. All of this happens preconsciously, before deliberate thought begins.

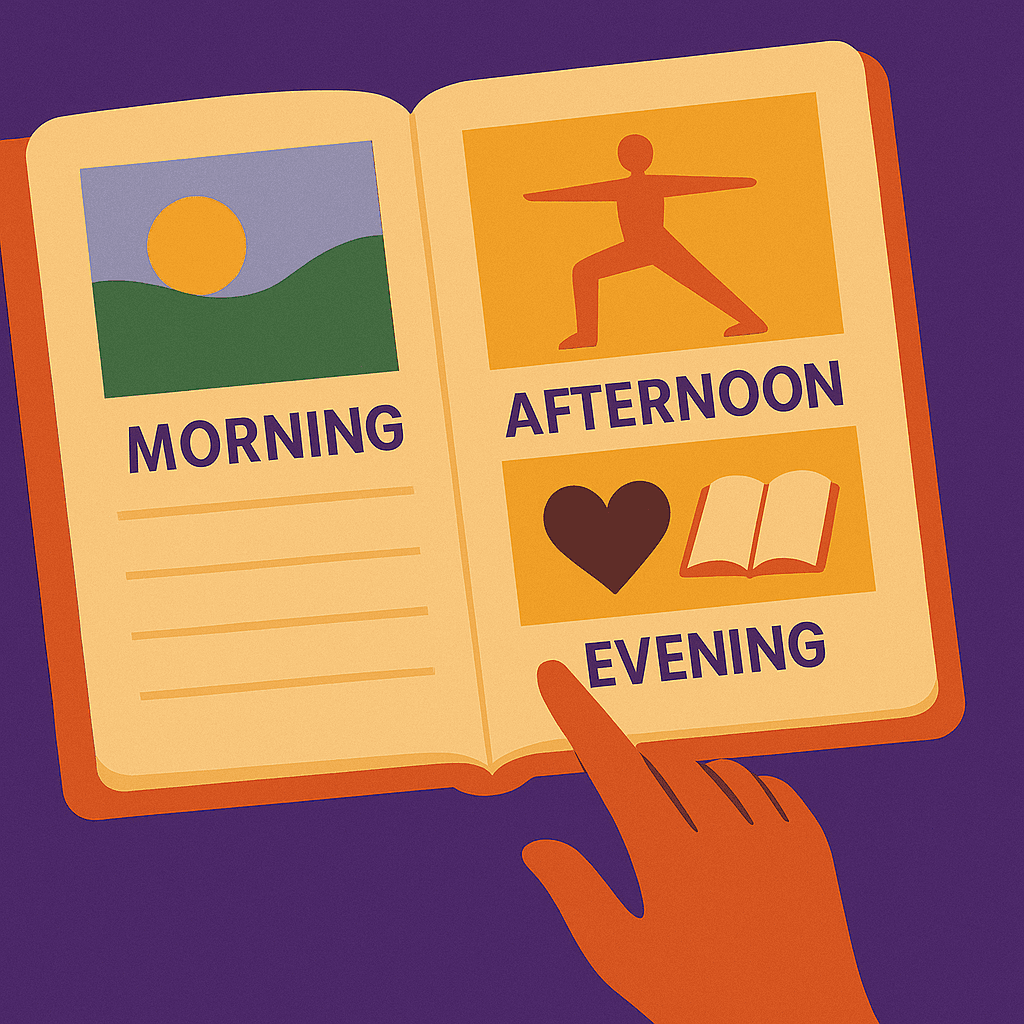

Text processing, by contrast, is sequential and deliberate. You must decode symbols, construct words, parse grammar, and build meaning sentence by sentence. Even skilled readers process text at around 250-300 words per minute, which means the morning routine list above takes several seconds to read and comprehend.

The visual version? Your brain grasps it instantly.

Your brain isn't a general-purpose computer that processes all information the same way. It's an evolved biological system optimized for visual processing in ways that text processing simply cannot match.

Roughly 30% of your brain's cortex is dedicated to visual processing, more than any other sense. This massive neural investment reflects evolutionary reality: for millions of years, survival depended on rapid visual pattern recognition.

Your ancestors who could quickly identify threats, opportunities, and resources in complex visual environments survived and reproduced. Those who couldn't, didn't. This evolutionary pressure created brains exquisitely tuned for visual information.

Text, by contrast, is a recent cultural invention, maybe 5,000 years old. Reading requires repurposing neural circuits evolved for other purposes. It's learned, effortful, and culturally specific in ways that visual processing is not.

A child can recognize her mother's face without training. Learning to read "mother" takes years of instruction.

Beyond memory and processing speed, visual representations provide what designers call "affordances", perceived possibilities for action that the representation suggests.

A text list of morning activities affords exactly one action: checking boxes. The structure suggests completion as the goal, execution as the relationship.

A visual representation of your morning affords multiple interactions: you can see the flow, feel the rhythm, imagine the experience, notice what's missing, recognize what matters, adjust the sequence, appreciate the beauty of intention.

The visual form invites engagement beyond mere execution. It supports what James J. Gibson called "direct perception", understanding that doesn't require explicit interpretation or deliberate analysis.

You don't think about what a morning routine image means. You see it, you grasp it, you feel it.