The Innovation Dilemma

Robert Kenfield | 7 mins read | December 3, 2025

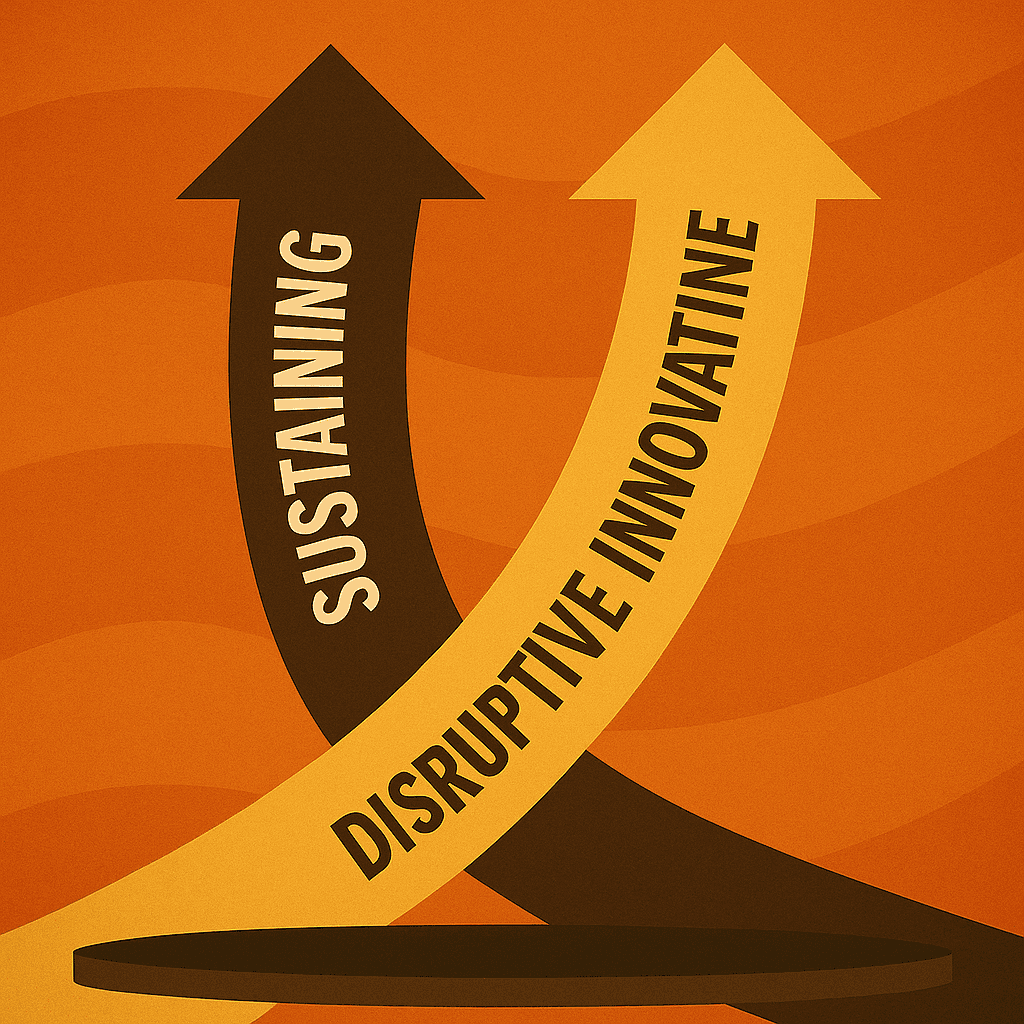

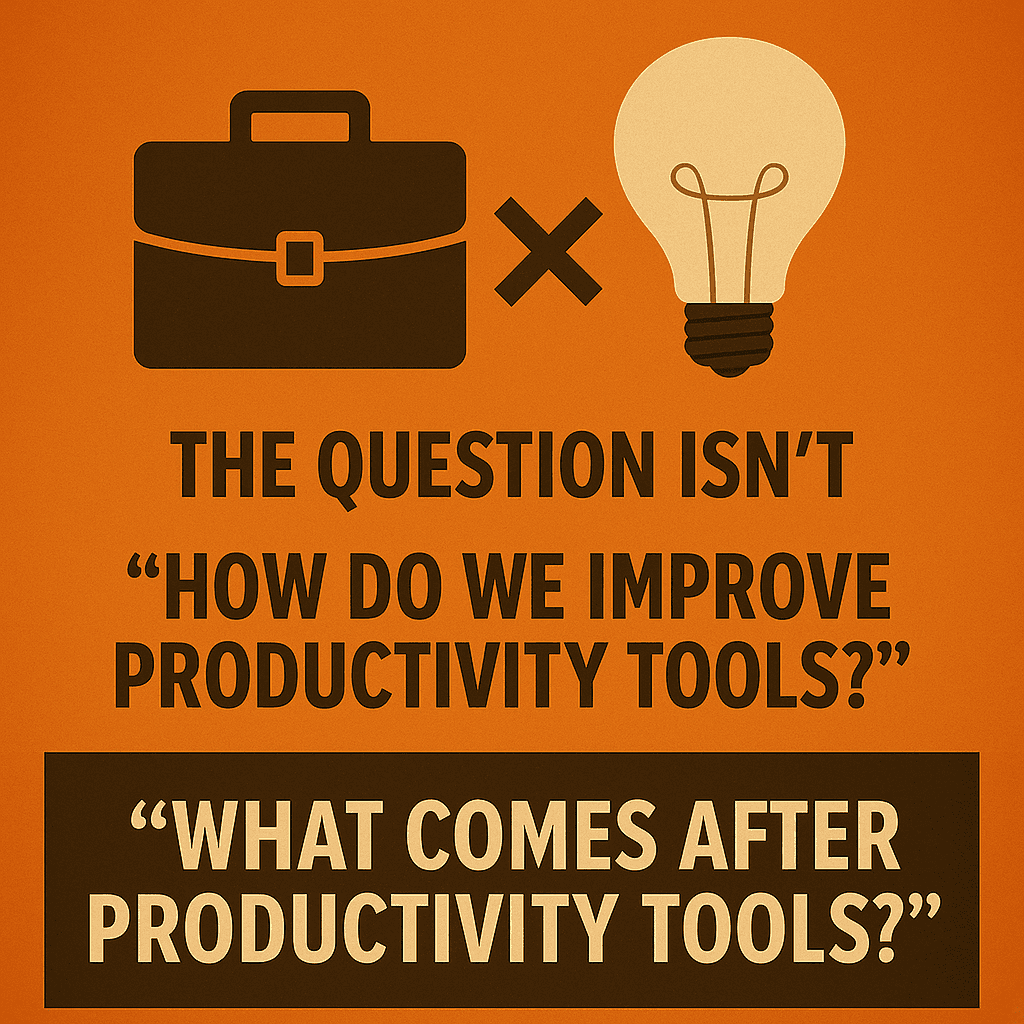

Christensen's groundbreaking research, documented in The Innovator's Dilemma, distinguishes between two fundamentally different types of innovation:

Sustaining Innovation improves existing products along dimensions that current customers value. It makes things faster, cheaper, more feature-rich, more convenient. It's what successful companies excel at.

Disruptive Innovation introduces new value propositions that initially serve different customer needs or create entirely new markets. It often performs worse on traditional metrics while being better on dimensions that incumbent customers don't yet value.

The dilemma: successful companies are structurally designed to pursue sustaining innovations and avoid disruptive ones, even when disruptive innovations better serve long-term customer needs.

This isn't stupidity. It's rational behavior given the incentives, resources, and organizational structures that made these companies successful in the first place.

Consider Google Calendar, probably the world's most widely used digital calendar with over 500 million active users.

Google employs thousands of talented engineers. They could, technically, rebuild Calendar around different architectural principles. They could add features for general time scheduling, visual planning, life area integration.

So why don't they?

Because Google Calendar's success is precisely defined by what it does now: coordinating meetings across organizations with reliable synchronization, preventing double-booking, and integrating with enterprise communication systems.

Google's enterprise customers, the ones who actually pay, value these coordination features. They want better meeting scheduling, improved time zone handling, enhanced integration with Google Workspace.

If Google's Calendar team proposed: "Let's fundamentally rethink how calendars work to support human flourishing rather than just meeting coordination," they'd face several insurmountable barriers:

Resource Allocation: Engineering resources are allocated based on expected return on investment. Improving enterprise coordination features has clear, measurable ROI. Experimental life design features have uncertain value and no proven business model.

Customer Risk: Changing fundamental architecture risks alienating existing enterprise customers who depend on current functionality. A failed experiment could cost billions in revenue.

Success Metrics: Product teams are evaluated on engagement, retention, and revenue growth, all tied to current product paradigm. There are no metrics for "supporting human flourishing."

Technical Debt: Years of feature development have created massive technical dependencies. The entire system assumes calendar grids, discrete events, and coordination logic. Rebuilding from scratch would cost hundreds of millions.

Google Calendar cannot evolve into a life design tool because its success is built on being an excellent coordination tool. The better it becomes at coordination, the more locked into that paradigm it becomes.

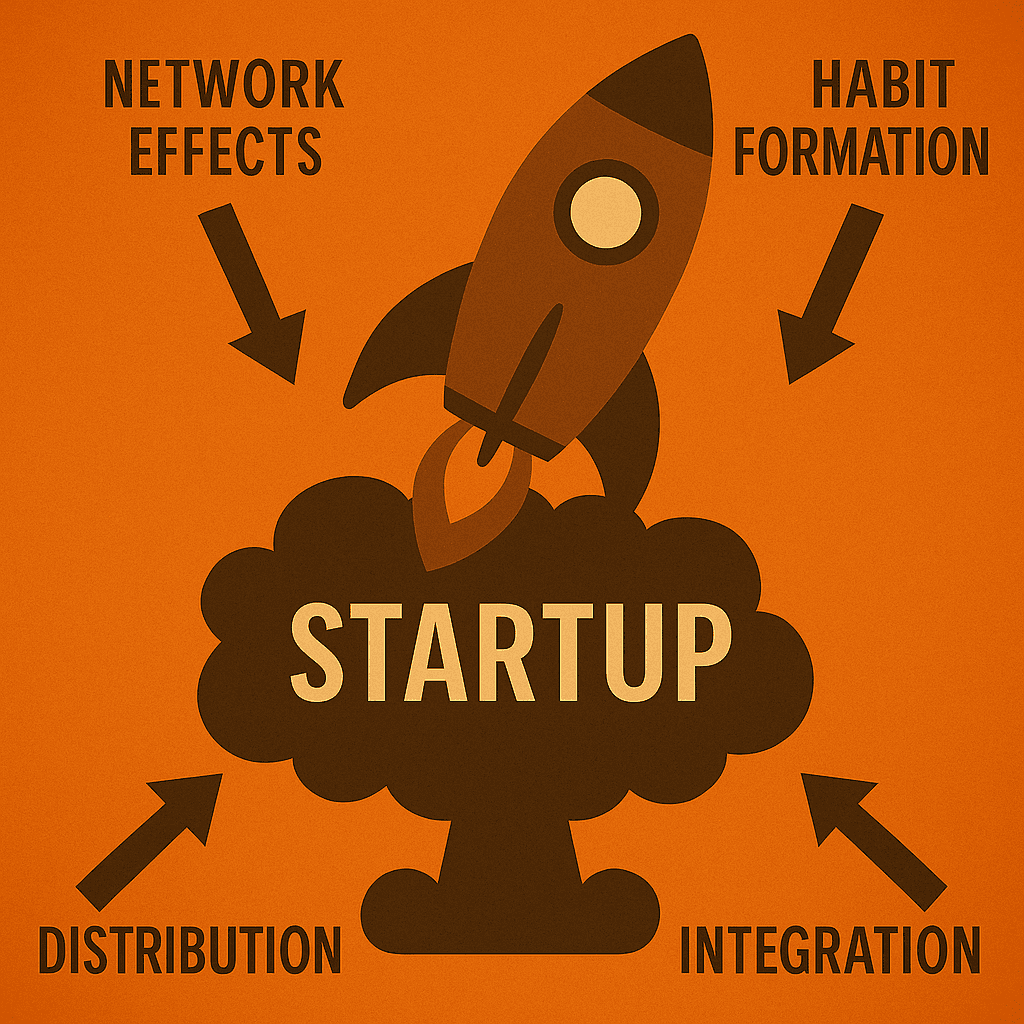

Notion represents a different flavor of the same dilemma.

Notion raised over $340 million by offering remarkable flexibility, databases, pages, blocks that can be combined in countless ways. It's beloved by power users who can craft custom workflows.

But Notion's flexibility is also its limitation. The platform is optimized for information management by sophisticated users who enjoy system-building. It assumes users want to create their own organizational structures from modular components.

This works brilliantly for its current user base: tech workers, students, startups, people comfortable with complexity and willing to invest time in setup.

But integrated life design requires the opposite: simplicity, immediate usability, and focus on living rather than system-building.

Most people don't want to design their productivity system. They want to design their life. They need tools that fade into the background rather than demand constant attention and configuration.

If Notion simplified to serve mainstream life design needs, it would alienate the power users who made it successful. It would lose its differentiation. Revenue would decline. Investors would revolt.

Notion can't pivot to life design without destroying what made it valuable to its current customers.

Successful productivity tools fall into what we might call the "feature creep death spiral":

Year 1: Launch with simple, focused functionality. Users love the simplicity.

Year 2: Competitors appear. Must differentiate through new features. Add capabilities users request.

Year 3: More competitors. More features needed. Each feature adds complexity. Original simplicity erodes.

Year 4: Now a "mature product" with hundreds of features. New users are overwhelmed. Power users are entrenched. Cannot remove features without angering someone.

Year 5+: Trapped between competing needs: power users want more features, new users want simplicity, enterprise customers want customization. Every added feature makes the fundamental problems worse.

You see this pattern in every mature productivity tool. Each started simple and focused. Each became complex and bloated through rational responses to competitive pressure and customer requests.

Nobody intended this outcome. But the structure of competition and growth forced it.